This article was updated on 17 October to take into account the rapidly evolving landscape surrounding the autumn Budget.

As new Chancellor Rachel Reeves gets to grips with her in-tray, the only thing that is certain is that there is a lot of uncertainty.

With various policy programmes announced in the recent King’s speech – and a mandate to implement them – the question on everyone’s lips is: where’s the money going to come from?

In Reeves’ speech at the end of July, she alluded to a £18bn ‘black hole’ in the public finances. In laying out her plans to plug this gap, Reeves refrained from announcing any tax rises, but did commit to spending cuts in some areas – such as scrapping the Rwanda project, and making fuel payments for pensioners means-tested. Those cuts, however, were partly offset by a public sector pay increase, and Reeves made it clear that more belt-tightening would be inevitable come the Autumn Statement. Keir Starmer’s ‘rose garden’ speech at the end of August took things further, with the black hole expanding to £22bn, alongside higher than forecast national borrowing, and warnings of a “painful” budget in October.

In recent days the black hole has jumped to £40bn and there have been leaked reports of ministers going over Reeves’ head regarding significant cuts to their departments’ budgets, which feel similar to former Chancellow George Osborne’s austerity policies. It seems that we are building to a painful crescendo.

Labour have already ruled out rises to income tax, national insurance, VAT, and corporation tax. The public is being stretched in every direction: a cost of living crisis; a historically high tax burden; and mortgage costs sky-rocketing (a shift which will hurt more and more people as they come off their fixed-rate mortgage deals). It would be a tough ask to call on people to pay more, when they have less.

Perhaps the government could borrow money to meet the shortfall?

This seems unlikely, as the government is not immune to high interest rates. National debt, in pound terms, is higher than it has ever been and with the cost of servicing those debts (interest) at its highest since 2008, borrowing more is not a burden any Chancellor would saddle the country with lightly.

No economist out there will envy Reeves’ position at the moment. Options are thin on the ground. Ruth Gregory, of Capital Economics, has said she expects the remaining fiscal pothole will be filled through a combination of additional borrowing and tax increases. And it seems she may be correct – in recent weeks, it has been rumoured that Labour will look to change how debt is defined (an interesting concept!), which signifies they may look to issue more bonds. Given that the size of the black hole has increased, this may be to help fill that extra gap.

The question is: which taxes? And how might this be done?

A Taxing Balance to Strike

Let’s take a look at some of the usual suspects – and how Labour might address them.

Inheritance tax has been the focus of many a newspaper article throughout 2024, but given the relatively modest level of revenue this raises and the limited will to drag more middle-income families into the inheritance tax regime, any major changes here would likely be political posturing. Labour could, however, look to modernise this area – one which has largely been neglected for the last decade. Read our recent article to find out how Labour may look to achieve this. Some commentators have since suggested that inheritance tax-relievable investments may be up for the chop.

The higher Capital Gains Tax rate on second homes could be moved back up to 28% from 24%. Again, this would likely not raise too much in revenue, but may indicate there is more pain for buy-to-let landlords to come. It is not infeasible to think that Labour will pick up where the Conservatives left off – continuing to increase the tax burden on investors with a property portfolio – as they look to make more homes affordable to first time buyers. We have written several articles recently covering whether property is a good investment or not and what you need to think about if you have a property portfolio.

Rumours have also been circulating that Labour will seek to increase Capital Gains Tax rates to match Income Tax rates. It is certainly a possibility and would typically target wealthier people as they will have investments. As we recently explained, this would be bad for business, which would be the antithesis to Labour’s stated desire to grow the UK economy.*

This leaves pensions as one of the last great tax-efficient bastions of personal wealth – and that means the tax relief you get on your savings could be about to change.

Tax relief on pension contributions: an example

One of the fantastic benefits that pensions offer is that when you put money into them, you get income tax relief on those contributions. This encourages people to save for retirement and provide themselves with future financial security. It is also a fantastic tool when it comes to reducing your tax bill.

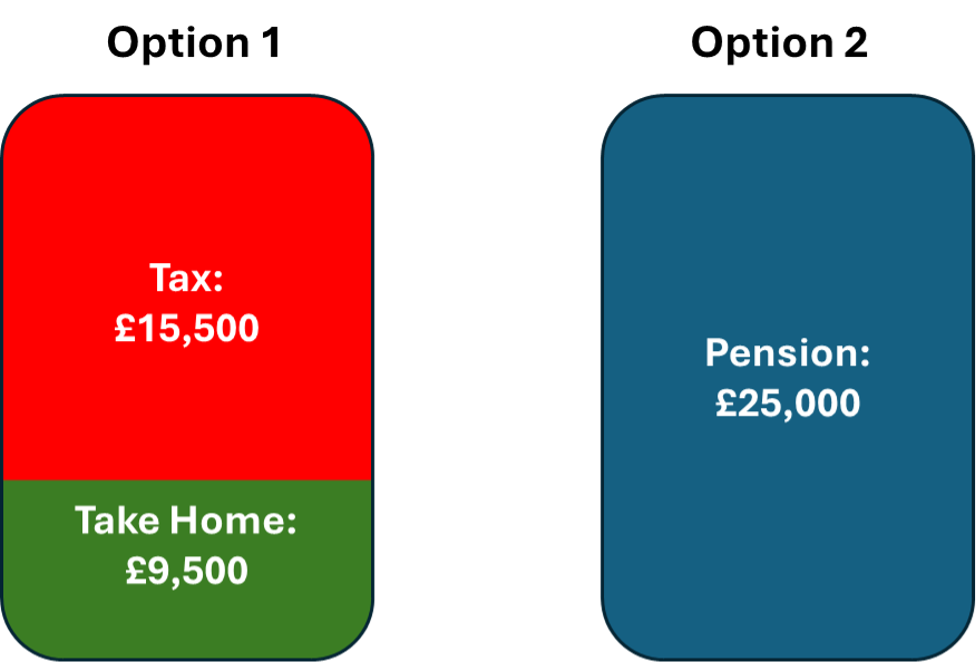

Let’s say – for example – you earn £125,000 pa. You will be well and truly caught in the ‘tax trap’. For every £2 of income you receive over £100,000, your tax-free Personal Allowance is reduced by £1, until it is lost. This means you are effectively taxed at 60% on your earnings between £100,000 and £125,140. You’ll also need to pay 2% in national insurance. All in all, of the £25,000 over £100,000 you have earned, you will be taxed £15,500 and only receive £9,500 of take-home pay.

If, on the other hand, you contributed that £25,000 into a pension, you could save up to £15,500 in tax – effectively a guaranteed return of 163% overnight.

How you’ll be taxed on the the £25,000 over £100,000 you have earned (Option 1) versus how you’ll be taxed if you put that £25,000 into a pension (Option 2)

There are, of course, limits on how much tax relief we can receive in this way – this is known as your Annual Allowance. Your earnings from work that can be added to your pension are capped at £60,000 (a recent increase up from £40,000 as of April 2024). This cap is tapered down if you receive income over £260,000. You can carry forward any unused allowance from the three previous tax years, meaning this year you could receive tax relief on pension contributions of up to £180,000.

This could well be the area that Rachel Reeves targets to raise tax revenues. Let’s be realistic and tackle the fearmongering that has been going on in the press: what the government will not do is ‘raid pensions’. Some people that we speak to believe that Labour will take money out of their pension pots to fill the national coffers. This is not going to happen. Any changes to pensions would have to be balanced against the risk of the future pension poverty timebomb (think of the phasing out of gold-plated final salary pensions over the last few decades). This could lead to an increase in the amounts employees and employers have to pay into pensions under the auto-enrolment rules.

In terms of raising tax revenue, Reeves could look to reduce the annual allowance (the amount you can pay in to your pension tax-free). Or she could reduce the rate of tax relief you will receive on any pension contributions you make, if you are a higher or additional rate taxpayer. Some commentators have suggested Reeves may look to bring in a flat rate of tax-relief at say 20% (current basic rate tax levels), meaning if you earn over £50,270 and pay into a pension via salary sacrifice, you could end up with an additional tax bill at the end of the year and having to do a self-assessment.

Interestingly Reeves recently refused to dismiss rumours that Labour will either increase Employers’ National Insurance Contributions or make businesses pay Employers’ National Insurance Contributions on pension contributions, claiming that Labour promised not to increase NI for employees, but did not promise such a thing for businesses. This could help to address a growing future pension poverty issue, but arguably does not match Labour’s manifesto commitment to get the economy growing. Again, Reeves has an extremely difficult and unenviable balancing act on her hands.

What else might happen to pensions?

- Labour has already committed to the very generous Triple Lock guarantee for State Pension recipients – but they have refused to match the unfunded commitment of the Conservative party to increasing their tax-free Personal Allowance.

- Labour could look to means-test State Pensions. Given they are willing to means-test winter fuel payments, this is not beyond the realms of possibility – and may in fact be necessary, given State Pensions are funded from current national insurance contributions. There was already an increasing gap between the level of contributions and the level of money paid out to pensioners, even before the Conservatives cut national insurance from 12% to 8%.

- Funds invested in certain types of pensions can typically be passed down the generations, free from inheritance tax. We see a big target painted on this area – it is an allowance that Labour could look to remove or reduce. Such a policy could be eased in by, for example, exempting existing pension pots from any policy change.

A limited window of opportunity?

If changes are on the horizon, then there is a very limited window of opportunity to benefit from:

- The reduced upper limit of Capital Gains Tax on property

- The existing Annual Allowance levels

- The ability to carry forward 3 tax years’ worth of unused Annual Allowances

- The current inheritance tax benefits pensions provide

- Putting your future financial security in your own hands, rather than relying too heavily on the State Pension, which will need to change over the coming years

What should I do?

Any future changes are likely to come with transitional protection for those that have prudently planned for their financial futures under the existing tax framework. That means that by acting now, you can significantly future-proof your pensions and other assets.

The topic of tax relief on pension contributions is a complicated and evolving area, and the cost of taking action and getting it wrong, or taking no action at all, could be hundreds of thousands of pounds to yourself and your loved ones.

Every scenario needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and as such, this article does not constitute financial advice.

If you would like to speak to an expert on what the October budget could mean for your situation and what opportunities are available to you now, please schedule a no-cost, no-commitment consultation with one of our financial planners.

Book a consultation

*The reason that Capital Gains Tax rates are lower than income tax rates is to reflect the risk that investors are taking when buying and holding an asset. They will also be taxed on the income that asset produces as well, which reduces the overall net yield. Increasing Capital Gains rates would deter people from investing and therefore from providing the funds that businesses need to flourish. This is also why Reeves’ hands are somewhat tied when it comes to reducing Business Asset Disposal Relief from entrepreneurs selling their businesses and increasing dividend tax rates to match income tax rates (not to mention dividends are paid out after Corporation Tax has already been paid).

Any money invested carries an element of risk and you are not guaranteed to get back the money you invested. This article does not constitute advice and you should consult your financial adviser prior to any action.